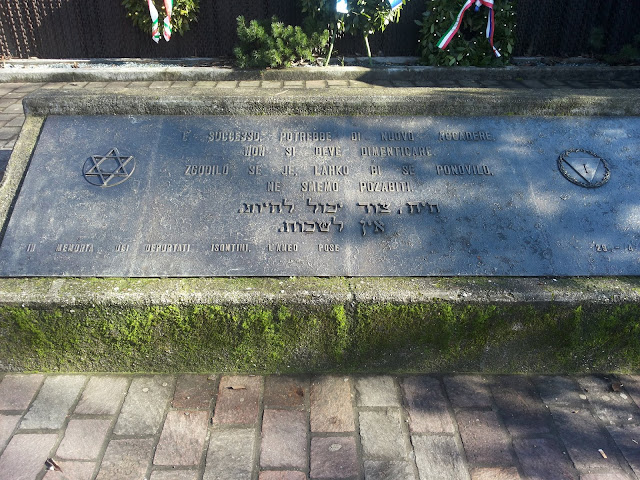

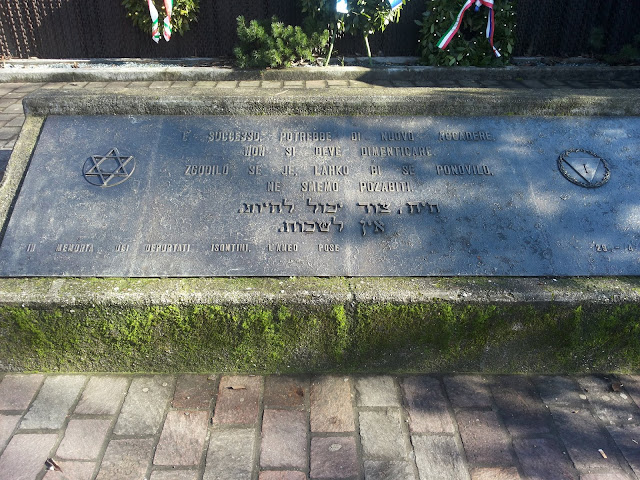

It must have been in 2003 that I went by train from Trieste to Gorizia with Brana and my daughters. At the station we set off to walk into the town, to visit the castle, and my relations at San Rocco. I was surprised to discover a monument facing the station to the Gorizian Jewish victims of the Holocaust who had been taken by train from Gorizia to Auschwitz. However, since then, despite several intensive searches on the internet, I have been unable to trace any mentions or photographs of that memorial.

More importantly, I was struck by the date recorded on that memorial for the round-up of Gorizia's Jews: 23rd November 1943. I knew that my mother and her mother and siblings had left Albania after the Italian armistice on 8th September 1943, when her father had gone into hiding, and I wondered how she had escaped deportation. As a 'mischling', or half race, she should have been arrested and sent to Germany, possibly to Buchenwald rather than Auschwitz, as happened to other mixed race victims. It seems my mother arrived in Gorizia in January, 1944, less than two months after that original round-up, whilst the Germans were still in charge of that area of Italy, now annexed to the Reich as the Adriatische Küstenland. People were still being arrested and deported, and I realise now that my mother and her siblings were just extremely lucky. When I told my mother about this I don't think the penny dropped.

"After the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943 and the occupation of northern Italy by German forces…"

"Il 23 novembre 1943, dopo l’occupazione del territorio da parte dei nazisti, una retata distrusse la comunità ebraica, deportando 73 persone ad Auschwitz, di cui solo due ne fecero ritorno."

[On November 23, 1943, after the Nazis occupied the area, a raid destroyed the Jewish community, deporting 73 people to Auschwitz, of whom only two returned.]

[My friend Luigi Corolli in Gorizia has kindly visited the memorial and taken these photographs for me.]

|

| Monument to deported, Gorizia. Photograph ©Luigi Corolli. |

|

| Monument to deported, Gorizia. Photograph ©Luigi Corolli. |

|

|

| Monument in Gorizia to a Jewish baby killed at Auschwitz. |

|

| The struggle by partisans in Gorizia to resist the German occupation in September 1943. |

|

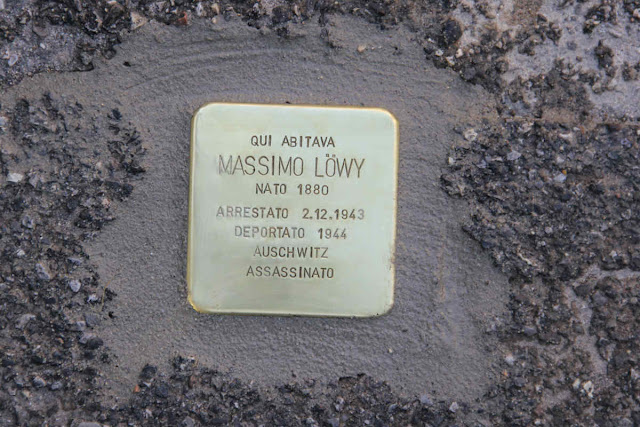

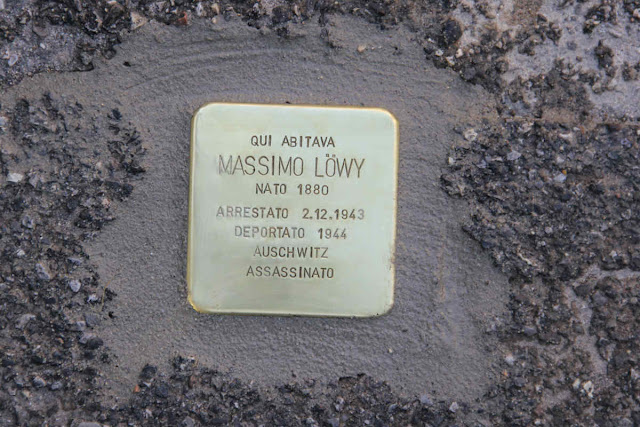

| A 'stolperstein' in Gorizia, remembering a victim of the round-up. |

|

| Another 'stolperstein' in Gorizia. Some Italian towns have refused them. |

|

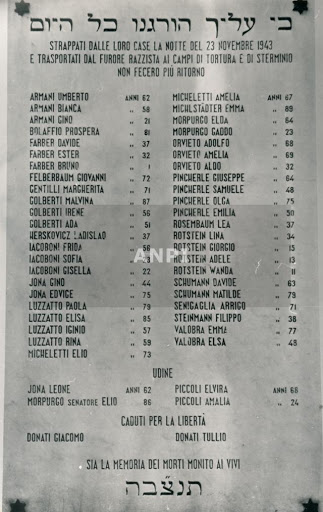

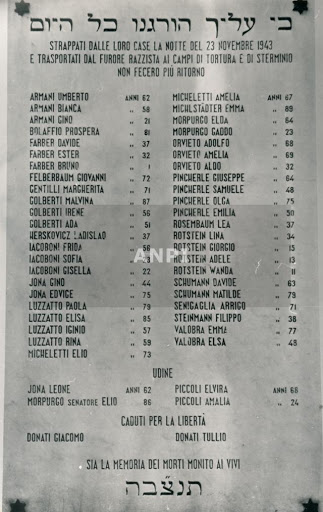

| Gorizian Jewish victims of the Holocaust. |

|

| By Пакко - File:Greater albania.JPG;, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10010229 |

This is my mother's account of the journey from Albania to Gorizia:

On the 8th of September, 1943, Italy, under General Badoglio, signed the armistice with the Allies, against the Germans' will. We were treated much worse both by our ex-Allies [the Germans] and the Albanians. No warning was given to the commanders in different areas of the war; the troops in Albania and Greece found themselves in the middle of a foreign country surrounded by hostile ex-allies and occupied ex-friends. No orders were issued by Badoglio and several divisions of the Italian armies found themselves in a dreadful situation. Some surrendered to the Germans; some fought and were decimated by our ex-allies. Mussolini had been imprisoned and Fascism in Italy was declared finished. Badoglio appeared to be the saviour of Italy, many think that he caused much more bloodshed and destruction in our country. The carnage of our troops by the Germans continued and the Julia Division, the elite of Italian alpine troops, was decimated and treated as labour workers.

|

| Italian soldiers in Albania. Photograph by Luigi Bazzani. |

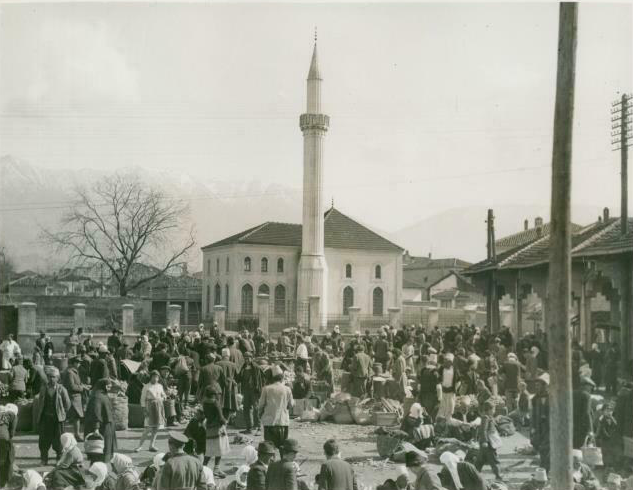

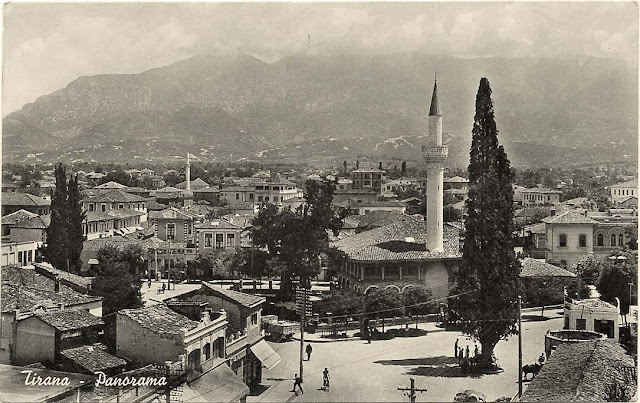

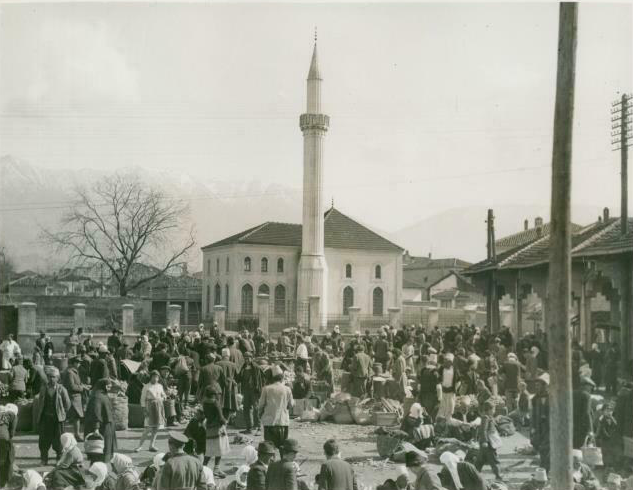

Soon after the armistice there began an even more fearsome period in our lives and each day was worse than the previous. There was no food available for us, the bombing increased, there were more attacks on Italian nationals and there were more executions in Tirana's market square. Death became a way of life and we were not shocked by the continual violence around us. We were young, my sisters and my brother, and we did not fully appreciate what was happening all around us. We used to go roller skating in a building which had been a Fascist ministry and was now abandoned; it had gorgeous marble floors and they were an ideal skating surface. Most days we went in the afternoons to play there. One afternoon I thought I could see more people going and coming around the area and I said to my sisters and brother that we would better go home earlier; I set off for what was only about five minutes' walk from the building. Luciana and Sergio said that they would follow after trying a new pattern they had learned on the skates.

I had hardly reached the building when I heard the sound of shooting; I ran to the window (we were on the fourth floor) to see if my sister and brother had followed me. I could only see a great deal of armed men swarming all over the area and there appeared to be two different bands as they were exchanging fire. I found out later that a group of Communist partisans had infiltrated the German lines and they been attacked by pro-German partisans. I was trembling and I was told off by my mother for not waiting for the others. While I watched I saw a young man dressed in a light-coloured jacket running and being pursued by a German on a sidecar; he was running toward our building and he was getting near. Suddenly the German aimed his machine gun at the retreating man and I heard the rat-tat-tat of the machine gun. A red pattern appeared on his whitish jacket. He kept on running and he seemed to reach the entrance of the flats. By this time there appeared several armed men and many soldiers. There was a great commotion as they entered the building in search of the injured man; every apartment was searched and when a door was not answered it was smashed down. All the men found on the premises were collected and put in the courtyard. By the time they reached our door my mother had become hysterical when they arrested my father, after searching our flat and finding nothing. The man was not found; he had disappeared as if by magic. Unfortunately, the troops and their followers were incensed and lined all the Italian men in the courtyard and threatened to execute them all in reprisal. All the women were crying and begging the soldiers to release the men; we were very sure that this was the end. Suddenly a group of German officers burst on the scene and I recognised an officer who was stationed near our home and to whom I had spoken twice in French. He came from Alsace-Lorraine and was not very much in agreement with Nazi ideas. Anyway, he was our saviour because he gave orders to release the hostages and leave us alone. We could not believe our good fortune and thanked him and his men for saving us. It may sound like a far-fetched story but it is the truth and the truth can often be stranger than fiction. We never found out what happened to the injured partisan; somebody in our building must have given shelter somewhere where nobody could find him. I hope he survived but the person that hid him endangered the lives of nearly a hundred people. Thank God he was not found! The morning after this I went to do the usual shopping to the market square; it was covered by hundreds of bodies lined out in rows. The red [Communist] partisans had all been taken and killed and their bodies were left for everybody to see and think about not defying the Germans; there must have been at least one hundred men stretched out on the pavements and square.

[My mother on another occasion was taken from her school with her fellow pupils to watch the hanging of captured partisans. Because they were hanged by slow strangulation boys would run and jump to grab them by their legs to shorten their suffering.]

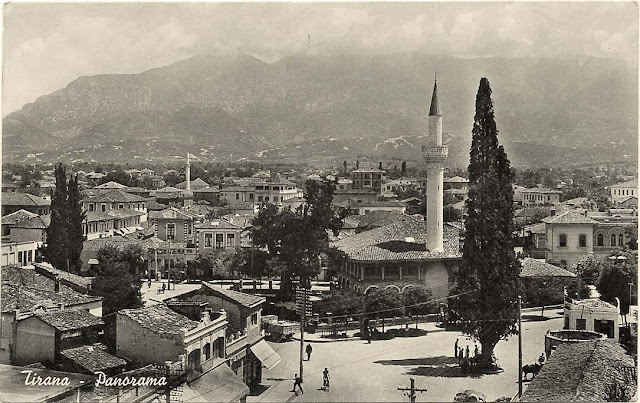

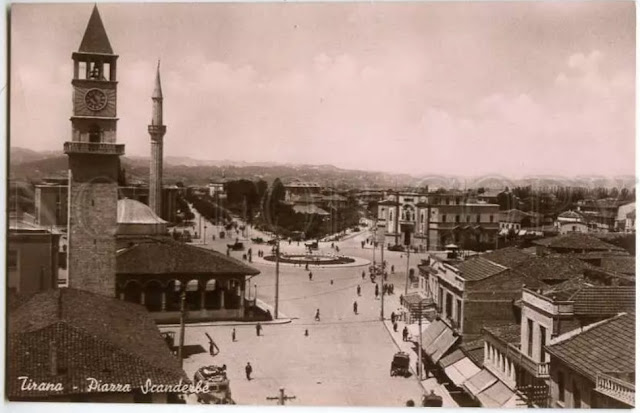

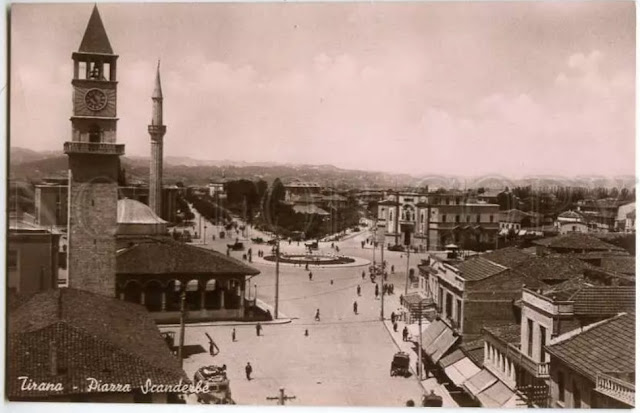

Tirana

|

| A view of Tirana. https://images.app.goo.gl/tCwiRRm2bQ2Je4JE7 |

|

| The main square in Tirana. |

|

| Tirana in 1939. |

|

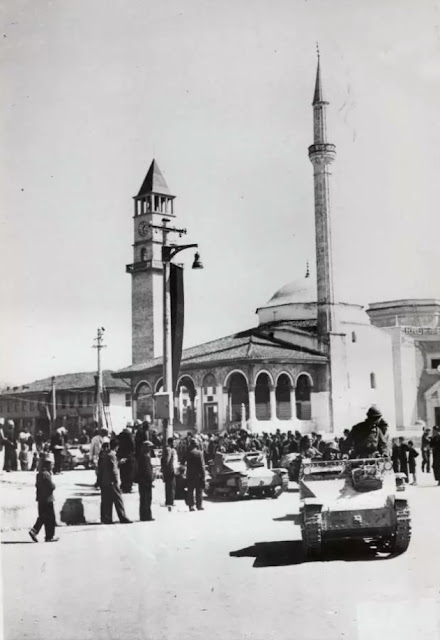

| The square in April 1939. |

|

| Skanderbeg Square during the Italian occupation. |

|

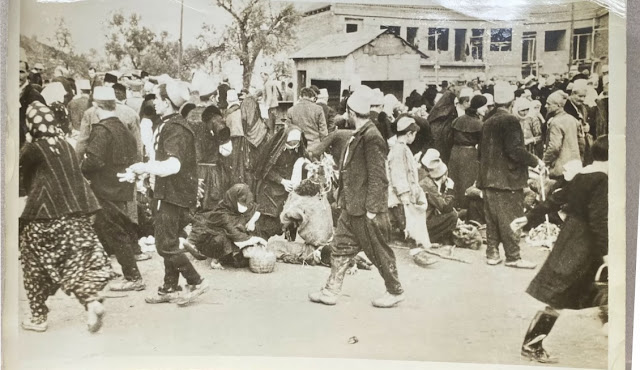

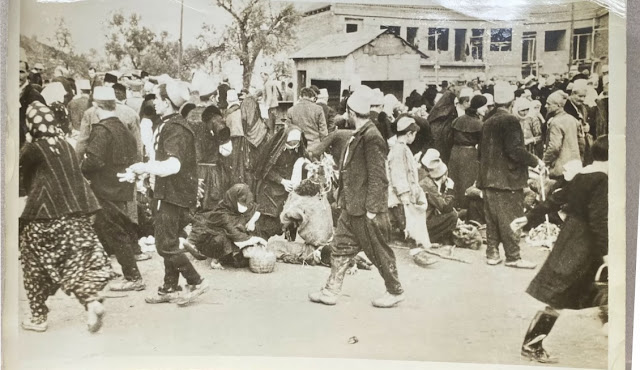

| Albanians in Tirana in the 1930s. |

|

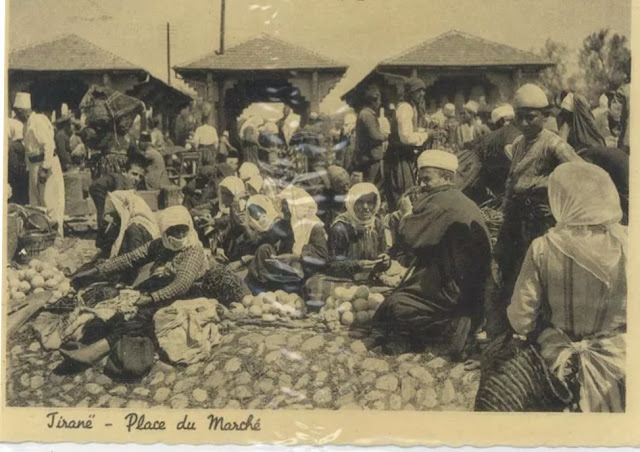

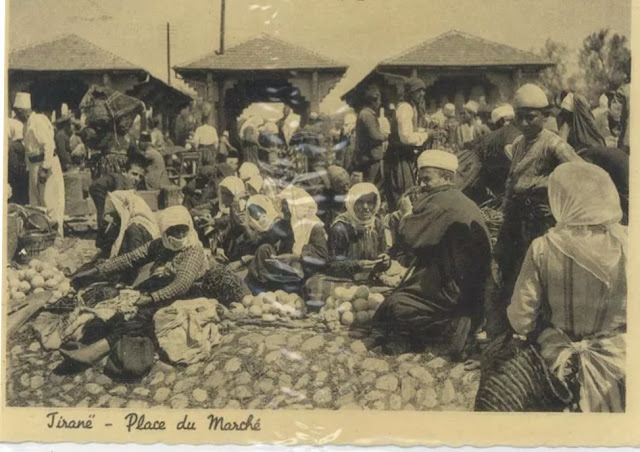

| Albanians in the market place in Tirana. |

|

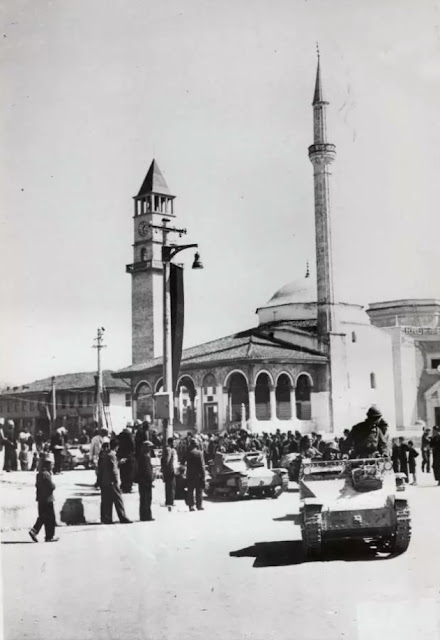

| Italian tanks in the square at the time of the invasion. |

|

| Italian tanks enter Tirana. |

|

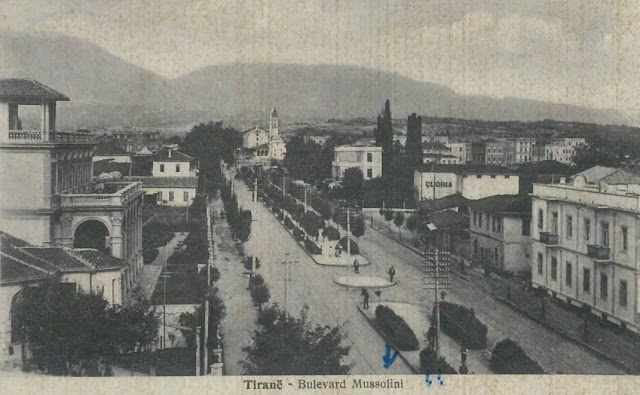

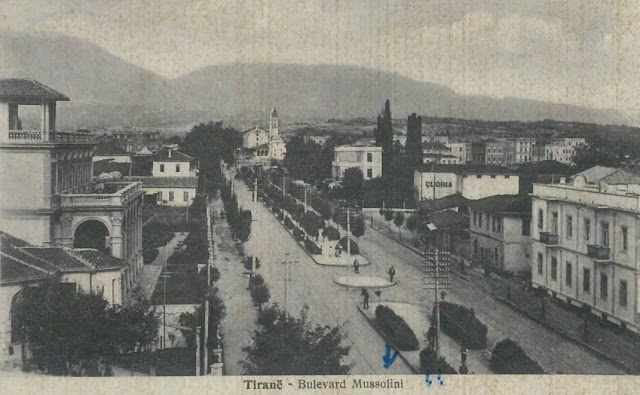

| A new main road in Tirana named in honour of Mussolini. It is now known as National Martyrs Boulevard. |

|

German soldiers in summer uniform in Tirana after the Italian capitulation – probably 1944.

|

|

| Skanderbeg Square in 2019. |

My Mother's Family in Tirana

|

| Tirana: the marriage of my great uncle Angelo Madriz. |

|

| The staff of the Tirana branch of the Bank of Naples. |

|

| The Italians invested in new building developments in Tirana. My grandfather on the left. |

|

| New housing and public buildings in Tirana. |

|

| A family picnic in Albania. |

|

| My grandfather in Tirana. |

|

| My mother's family home in Tirana: their Pomeranian dog Lola. |

The Departure from Albania

After all these episodes my father and mother decided to book a passage on the next ship to Italy. We were due to leave on the 14th of November, 1944 and we sold all our possessions and obtained some gold currency, the only thing that would be worth something anywhere and was easy to carry. Naturally, they took advantage of the situation and gave us very poor prices for our goods.

[My mother told me that she and her mother and sister had to hide the gold coins between their labia in order to smuggle them.]

We were all ready when the wife of my father's cashier was taken ill with nerves; her condition was bad and my parents decided to let them go in our place and wait for the next sailing. The ship was within reach of the Italian coast when it was sunk by British submarines; my father's cashier was one of only three survivors who swam to the shore. Once again we had cheated death and lived to fight another day. I can only remember that we could not go on another boat because all sea crossings were stopped after this disaster and we had to resign ourselves to remaining in Tirana indefinitely.

[This may refer to the sinking of S.S. San Marco on September 9th, 1944. "On September 9th, 1944, the Italian steamer San Marco, with some 250 passengers and soldiers on board, was attacked by allied bombers and destroyed by bombs and gunfire, while attempting to enter the port of Pirano, off Porto Savudrija. In an attempt to save as much as possible lives, captain Millo Rassevi grounded his ship. In total, 154 persons were killed, including women and children. Read more at wrecksite: https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?186077"]

Things became worse and worse all the time and food became in even shorter supply. We were treated very badly both by the Germans and the Albanians. We had to use our wits to survive and I, being the eldest, had to do all kinds of crafty and dishonest things to help us. My father was the bank manager at the Banco di Napoli and he did not know that his eldest daughter was at the Ministry of Supplies (a few doors up the street) claiming to be a refugee from Koritza and asking for food coupons and obtaining them. I do not know to this day how I managed to convince them that I was Albanian and from Koritza!

Time passed and, at last, in January 1944 we were repatriated by the Germans. We left Tirana by truck one cold morning in January and the last sight of the square in Tirana will forever be in my memory: the last thing I saw, was the body of a young Albanian partisan hanging by his neck in the main square of Tirana. I remember his face, his blackened tongue hanging out of his mouth and the white shroud in which he was enveloped.

[This gave my mother recurrent nightmares for several years. She once opened a door which had a white garment hanging on the back: a memory which had traumatised her.]

It was a very strenuous and hazardous journey; it lasted for two full weeks. We started the journey by lorry with three German guards with us. On reaching the border between Albania and Yugoslavia we met with thousands of Italian troops who had been taken prisoner by the Germans after the signing of the armistice. The majority were members of the crack Julia division of Alpine troops. They were in a pitiful condition both mentally and physically. They were clearing the snow in sub-zero temperatures and they were begging for bread. We managed to throw some bread which often landed in snow and slush but they retrieved it and ate it all ravenously. They shouted messages, but we were not allowed to stop. One of the guards must have felt some compassion because he threw some cigarettes and some food. We continued our journey on a train which we boarded on the border. It was a very long train and we shared it with hundreds of soldiers who were going to Budapest. They travelled in the carriages, we had to manage in the animal trucks. We were very crowded and only had straw to sleep on. It was a very cold winter as we travelled through the barren areas of Montenegro, to Hungary, Austria and eventually finishing our journey in Venice on the morning of 19th January,1944.

We had been through Budapest - we stopped the night in Buda - where we were treated very well by the Hungarians who fed us on goulash, rich milk and rum. While we were stopped for several hours in Buda we saw hundreds of Allied bombers flying over, probably on their way to Germany. We trembled with fear because several hundred German soldiers were travelling in our train and could be seen shaving and eating outside the carriages. The only good I remember about that journey is the wonderful behaviour of all the Hungarians.

As we entered the station in Venice the air-raid alarm was going and the station was deserted. We were disappointed: we had hoped to receive a pleasant welcome after all we had been through. We felt neglected and forlorn,and very, very tired.

Eventually we were taken off the train and directed to different queues, for food coupons, refreshments, and travel tickets for the train to Gorizia, where Zia Maria, my mother's eldest sister, was waiting to welcome us.

We were met at Gorizia by my aunt and her children: Livia, the eldest, who was about my age, Ada and Attilio. We had never met before, but we soon became very friendly and managed to make the best of a bad time. I cannot now remember the details of the house and where we slept, but I well remember that our bedroom window faced the garden to the rear of the house.

|

| I am unable to retrace my mother's journey from Albania via Buda to Venice. |

I suspect the route taken was from Shkodër in Albania to Podgorica in Montenegro, then via Belgrade and Subotica to Budapest. From there they could possibly go via Zagreb to Ljubljana and Trieste, or through Austria.

|

| A recent map of railways in the Balkans. |

Living in German-controlled Gorizia

|

| My mother with her mother and siblings at my great aunt Maria's home in Gorizia at via Aprica 19 towards the end of the war. |

|

| Gorizia, 1944. |

My grandfather made his way somehow to Gorizia, arriving there while the city was still under German occupation, as my mother records:

We struggled for several months always thinking that we had still no news of my father whom we had left behind in Tirana. We prayed every night for his safe return and worried about his position as a 'Jew'. Conditions were very harsh in Gorizia during the winter of 1944 and the lack of news was having a very depressing effect on my mother; we were too young to be of much help. One night I was awakened by a noise at the window and I was very scared, thinking about burglars and Tito's partisans. My mother was quite calm and said, 'Don't worry, it's daddy.' I will never know how she knew, she just ran to the window, opened it, and cried for joy as she held my father in a long embrace.Within a few weeks my father arranged for our move to Milan where he had found a position through contacts, and also an apartment in the centre of Milan. We were sorry to say goodbye to Zia Maria and all our other relations in Gorizia and we arrived in Milan on a cold, wet, winter evening during an air raid. We sat at the corner of Via Meravigli on our suitcases, while my father went to find the owner of the flat to collect the keys. We really looked what we were: refugees – dirty,tired and bewildered. People stared at us and turned to look again. We felt very, very sorry for ourselves and rather worried about what was to come. I do not remember much about this period of my life because in the continuous turmoil only odd incidents come to mind. On the night of our arrival Milan was bombed with incendiary bombs which caused many deaths and much destruction. Later we moved to Cusano-Milanino, which is where we lived when the Germans surrendered.

My Grandfather, Silvio Schiff, in Salò

During all this time my mother, grandfather and her siblings were at great risk and I have no idea how they survived undetected. Families who sheltered them also risked their own lives. There are similar untold stories concerning the survival of his father in Salò and his grandmother in Milan.

"With the police order no. 5, approved on November 30, 1943, the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (RSI) [of Salò] established that all the Jews of Italy had to be arrested and interned into concentration camps, while all their goods had to be confiscated. Between the end of 1943 and the summer of 1944, hundreds of Jews were arrested by Italian authorities and deported into Nazi extermination camps. By analyzing the ways in which the administrative authorities of the RSI applied the police order No. 5, this essay provides an answer to the question: which was the Italian way to the Shoah?"

http://e-review.it/stefanori-niente-discriminazioni

Matteo Stefanori, “Niente discriminazioni”: Salò e la persecuzione degli ebrei, "E-Review", 6, 2018. DOI: 10.12977/ereview267

|

| Löwy was born to Jewish parents, lived in Italy on Lake Garda from 1905, settled in Salò in 1936 and was arrested there in 1943 and deported to Auschwitz, in the same convoy as Primo Levi. |

|

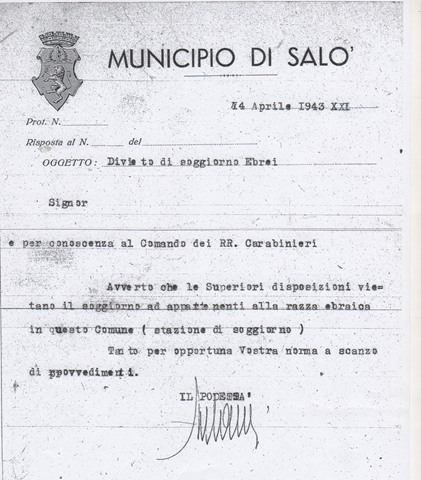

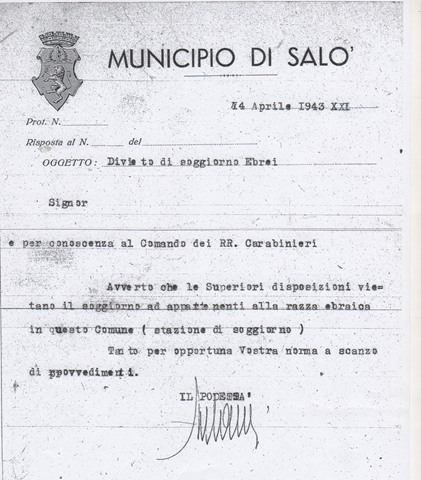

| Somehow my great grandfather evaded this order banning Jews from Salò. |

|

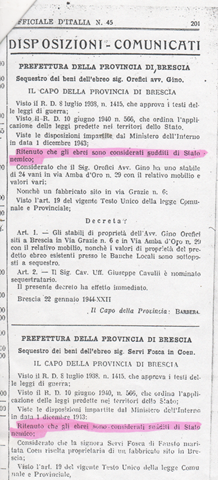

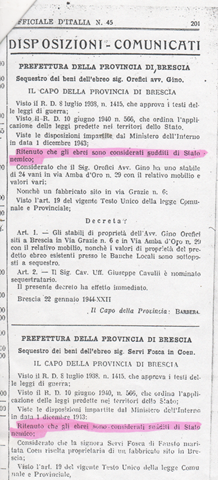

| Announcement that Jews were to be considered enemy aliens. |

I have written to the Brescia branch of the National Association of Italian Partisans sharing the story of how my great grandfather allegedly escaped the round-up of Jews in Italy, and requesting guidance on finding further information. They have replied, informing me of the book "La capitale della RSI e la Shoah. La persecuzione degli ebrei nel bresciano"

by Marino Ruzzenenti. I have ordered a copy.

|

| My great grandfather, Silvio Schiff, who survived detection in Salò throughout the war and the German occupation. |

I wrote this over twenty years ago:

As for my Jewish-born great grandfather, he survived the whole war living in Salò. Initially the fact that he had been one of the earliest members of the Fascist party in Salò helped protect him. This membership seems surprising to us now, but at the time many Jewish people and other ordinary citizens were committed adherents, believing in the then equivalent of 'law and order'. My great uncle Umberto told me that whenever there was any threat to his father, he would be hidden in the local hospital on strict quarantine. The truth is that he was still lucky: after the Italian armistice, Germany took control of Italy, and there was no longer any hesitation in removing the sick or the elderly from hospitals and sending them to death in Germany. No doubt it helped that my great grandfather's sons by his second wife were in the armed forces. Gino fought towards the end of the war, steering minisubmarines to attack Allied boats. Umberto was eventually knighted, becoming a Cavaliere della Repubblica for his work for seamen and their families. He was in the navy before the war, and naturally continued through the war.

Today, 28th february 2020, I received my copy of Mario Ruzzinenti's book, and on page 213 there is a list of jews in the province of Prescia which was forwarded by the prefect on 3rd November, 1943, to the Germans. My great grandfather is 62nd on a list of 90 names.

My Great Great Grandmother, Emma Finzi, née Teglio, in Milan

|

| Emma Teglio, wife of Costantino Finzi. |

My great great grandmother, Emma Teglio, the wife of Costantino Finzi, also survived the war, to die when I was about three years old. She had been living in Genoa, but I have no idea how she survived the war, presumably in Milan. Her name is recorded in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Holocaust Survivors and Victims database as follows:

It should not be underestimated how great the risks were for those helping or sheltering Jews. Under the German occupation a reward of 5,000 lire was offered if people denounced Jews. This would be approximately £2,000 now. That was the price of a man; women and children were worth 2–3,000 lire, while a rabbi was worth 10,000 lire or more.

Some relevant quotes:

"The Germans deported 8,564 Jews from Italy"

"All those doctors who played a part in the … deception knew they were risking their own lives; one slip up could have cost them all dearly."

In addition to his courier services, Batali also courted danger by hiding his Jewish friend Giacomo Goldenberg, and Goldenberg’s family, in an apartment Batali owned in Florence. “He hid us in spite of knowing that the Germans were killing everybody who was hiding Jews” Giorgio Goldenberg, Giacomo’s son, later recalled: “He was risking not only his life but also his family. Gino Bartali saved my life and the life of my family. That’s clear because if he hadn’t hidden us, we had nowhere to go.”