I've already written about times in my life when I felt rejected or an outsider, but there were other times when I felt a sense of acceptance. Surely I felt accepted when I was born, my parents' first son and all my grandparents' first grandson, and born less than ten months after the death of my sister. As one of six children I could not claim much of my parents' time and attention though. Nor really could I claim much of my grandmother's, but my paternal grandmother was there for me as a child. We spent weekends with her and my grandfather, had holidays with them. Indeed, pretty well all of my holidays were spent with my grandparents, save the trip to Italy in 1956. My grandmother accepted me just because she was my grandmother, and I was always grateful to her for that. She gave me space in which to develop and to play, she let me read voraciously, as much as I wanted. At the farm I played out on my own in the fields and in the woods, messing in the stream and down the river, on my own for many hours at a time and for days on end. She fed me, I helped with tasks in the kitchen and on the farm, and we went on outings on coaches. It was a very benign acceptance, without judgement, with no strings attached, no expectations and no real demands. She would answer my questions, share her stories, discuss with me. She had no pretensions, she was educated in a village school in Cheshire and was a decent, honest soul. We later sometimes slept in adjacent rooms - in the farmhouse my bedroom was reached through her room - and I would hear her mumbling her prayers at night.

I certainly hardly felt any sense of acceptance at primary school, or even at the grammar school, until I was in the Sixth Form, and then I latched on the the boarders, and sometimes joined them at the weekend. I became a prefect, and had the honour, or I took it as such, of being known by my forename and not by my surname. I don't think any other boy of my age had that distinction. Younger boarders befriended me and appreciated my friendship. I became assistant stage manager for school productions of Gilbert and Sullivan and Shakespeare, and enjoyed being accepted for my practical skills. Similarly it raised my morale to be so appreciated and accepted by the sacristy sisters at the Cenacle Convent. Sister Waite and Sister Burns were good friends to me and enjoyed my help and my company.

I didn't settle easily into university life, and it wasn't till my second year that I began to grow a little in self-confidence, but it was at the end of my second year that I had the wonderful experience of training in France as a moniteur, the term then used for a helper in a youth camp. The training at the course at St Jean les Deux Jumeaux was exciting. We were an international stage de base, with participants from all over the world. I excelled in the activities, I was able to flourish in the medium of a different language, and I also celebrated my twenty-first birthday whilst on the course. What could have been a lonely disappointment was a wonderful celebration, thanks to the other participants. I went from the course to work in the Jura at St Pierre en Grandvaux, near Geneva, with Père Paul Corand, and I worked with full commitment with the young boys at the colonie. It was a memorable month.

Being accepted for jobs always felt good, whether as a part-time librarian at Hulme Public Library when in the Sixth Form, or a an assistant in menswear at Kendal Milne's during the January sales.

I t was good to feel accepted when I got a job as a lecturer at Hertfordshire College of Building, not just for the teaching this entailed, but for living in a very male world and developing my male identity. I enjoyed working with the students, of all abilities, including taking them on residential courses and activity weekends. It is a surprise and a pleasure that I am still friends with some of them now.

My work for seventeen years at the museum in Exeter was not world-changing, but it did often touch young people's lives, and for the better. The work was often repetitious and even boring, but the enthusiasm of the thousands of young people was always rewarding. I have often quoted the young visitor to the museum who said, 'Mr Gent, you're the nicest man I've ever met.' My work with the WEA was also rewarding, in that it gave me the tools with which to touch people's lives for the better in many ways. I met some wonderful people who became tutors for my courses, and they not only touched many learners' lives, they became friends, and stayed in touch, including during my recent long stay in hospital.

When I left my lectureship after five years and went with my partner to Israel it was a new phase in my sense of acceptance. Firstly, to be accepted by my partner was a turning point. Secondly, to live and work in Israel, and to be accepted for both, was a moving and rewarding experience. At our first kibbutz we were accepted for our work, at the second for our skills in learning Hebrew, and at our third placement, in the northern development town of Ma'alot, I had the professional satisfaction of working as assistant borough engineer initially, later working on my own, and of working with young Jewish volunteers who came there in the summer. It was also in Ma'alot that I was taken under the wing of the local Jewish community, who taught me so much about my roots, my religion and my culture. I was so lucky to have that life-changing experience. When I later became involved in the Exeter jewish community I was able to make use of all those wonderful experiences to help rebuild Jewish life in Exeter. Some of that continues, but changes over the past decade have meant that the original flavour, very much inspired by 1980s Israel, has now gone, and a much more English, even Anglican, atmosphere often permeates the present-day community.

Over the past eight years I had the remarkable and special experience of being welcomed by friends who were gay, and whose friendship proved rewarding and moving. I discovered friendship as I had hardly known it before if at all. I shared so much, I felt safe, I enjoyed trust and support. I felt a sense of brotherhood and camaraderie; that was something I'd always wanted throughout my life.

At the same time, I was coming to terms with the two bleeds in my cavernous angioma. I was fortunate that despite two major seizures I was affected by none of the symptoms that affected others. It was thus that I became a trustee of Cavernoma Alliance UK, and I was appreciated for my work there. I was touched by the treasurers's appreciation of my ability to chair meetings, by his recognition of my skills, and by his sincere friendship.

Monday 30 January 2017

Friday 27 January 2017

The Dolls' House

We have two dolls houses. One is modern, made by my father's cousin Barry Shaw for my daughters. This one is much older, and we have gradually furnished it over the past twenty five years.

Our other doll's house, made by Barry Shaw, my father's cousin. We named it Barrington Court in his honour; his full name is Frank Barrington Shaw.

Thursday 26 January 2017

My Parents' Marriage

Whilst sorting out my old files and correspondence I rediscovered these letters that cover the period in early 1946 from when my mother discovered she was pregnant to her arrival in England and her marriage on June 29th, and the birth of my parents' first child on 4th October.

|

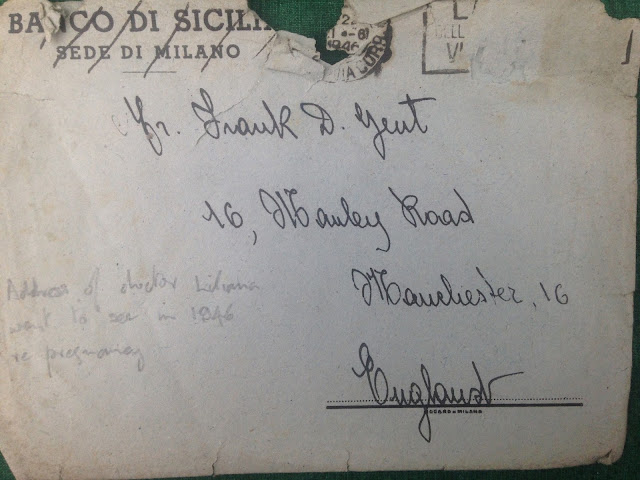

| The address of the doctor who confirmed my mother's pregnancy to her |

My mother wrote this note on some paper that must have been from her father, but indicating that he had resumed his employment at the Bank of Sicily. He had been dismissed from his post at the bank six years earlier as a Jew. My mother told me shortly before she died that although he was able to reclaim his post after the war he was warned not to make a fuss or attempt to claim any compensation.

My father wrote to my grandfather asking for permission to marry my mother. My grandfather's reply has become a family legend. It shows perception, understanding and realism.

Of course, my grandfather at this time was quite unaware of my mother's pregnancy, and attempted to delay the marriage to the following year. There were good reasons for this, not just those he enumerated. I suspect that he hoped that time would allow them to reconsider a hasty decision.

The draft of my father's reply to his future father in law. Written in pencil, it is very faded. I believe it is from April, 1946, and in reply to my grandfather's letter of 12th April, 1946. This transcription has been made by my sister:

I am writing to thank you for your most interesting letter. There has been a slight delay because unfortunately it arrived at my home after I had returned to Germany, but my parents readdressed your letter and it arrived here last week. I was delighted to hear from you, Mr Schiff, and I have been awaiting your letter anxiously, though not without a certain amount of trepidation! However, you have set my fears at rest with one of the finest letters it has ever been my pleasure to read. I am very grateful to you for being so frank and honest, and yet also kind and sympathetic.

I think that by now you will have received the news you were waiting for from Manchester and I sincerely hope that was satisfactory. I am certain in my own mind that the information you have received regarding myself and my family will have been reassuring. I would also like to assure you that I fully appreciate the difficulties which will lie before Liliana and myself. But, Mr Schiff, I considered the matter very, very carefully before I proposed marriage to your daughter and I am completely confident that our marriage will be a success. Believe me, I realize that if I had even the slightest doubt in my mind it would be inviting disaster to marry and, to use your own words, it would lead to the ruin of our two lives, and the consequences would be far worse for Liliana than for myself. Because, as you know, Liliana and I spent a great deal of time together (more than you approved of I fear) during the seven months I was in Milan, and I think we understand each other. I would like to tell you what in my opinion, are Liliana’s merits, because that is the reason I wish to marry her. Naturally, being a man I was first attracted by liliana’s beauty. I am well aware that there are many who would consider her attractive, but I am not concerned with what others may think…..I think she is beautiful. Of course, mere physical attraction, though necessary, is not a sufficient basis for marriage. Beauty fades, and it is then that a marriage is proved a success or failure. As I came to know Liliana more, I realized that she had many other attractions. She is hones, faithful, intellent, adaptable, has had a very good education, and she is devoted to me, a devotion which I entirely and completely reciprocate. Liliana also loves children, which is most important, because I believe that a marriage is incomplete without children and we both desire a family.You say that Liliana’s temperament is also one of her defects, but I personally admire her impetuosity. There are many other things but they all amount to the same. Liliana and I understand each others defects and appreciate each others merits and we are convinced that our married life together will be both happy and harmonious.

You have also mentioned the differences of race, religion and habits, but I discussed all these with Liliana before I proposed to her. I wish to marry Liliana as she has all the qualities that I desire her to have as my wife and the fact that she is Italian is immaterial. I also believe that Liliana has consented to be my wife for the same reasons, and it is not important that I am English and not of the same race. I do not think that I am wrong in assuming that the question of religion is an important one which only Liliana and myself can settle, as it concerns only us. If we had any difference of opinion of course it would inevitably lead to a breakdown of our marriage, but we each respect the other's religion and we are satisfied that it will not have any adverse effect on our married life.The English habits and way of life does not differ greatly from your own and I have no doubt that Liliana will quickly accustom herself to the slight change. Also, Liliana has an excellent knowledge of the English language, and it will be a tremendous help to her when she arrives in England.Well, Mr Schiff, I hope I have succeeded in convincing you of my sincerity. I am certain that our marriage will be lasting, happy and of course, what Liliana and myself desire more than anything in the world.

During the past month I have been trying to get permission to come to Milan, but I regret to say that all attempts have failed. I have tried every way, but my last hope disappeared a few days ago when S.S.A.F.A informed me that there was no possible chance. I was bitterly disappointed, because as you now (with your approval), I desire to marry Liliana as soon as possible, but if I could not come to Milan I thought we would have to wait at least a year. However, I received some news yesterday which has altered everything. To my surprise and joy, I am to be released from the Army immediately, because the Government consider that my civilian work in England is more important, so next week I return to England. My future is now secure and I can offer Liliana the home and happiness she desires. I earnestly hope that you will consider my request for an early marriage, because both Liliana and I would like to start our married life together and settle down in a home of our own. I personally, would have preferred to be married in Milan, but unfortunately, that is impossible. However, the British Government will permit Liliana to travel to England, and I would like her to come if you will permit it. You cannot imagine how much I am suffering because of our separation, and if you will sanction Liliana’s journey to England and our early marriage, Mr Schiff, you will earn my heartfelt thanks and gratitude.In the anticipation that we will have your permission, I will prepare for Liliana’s reception when I arrive in England!I pray that I shall not be disappointed.Once again I thank you for your kind and fatherly letter, and send you and your family my very kindest regards and best wishes.

Yours sincerely

|

| Release of my father from the army for civilian reconstruction work in England |

|

| The Rev. Fred Ethell, Rector of St Margaret's Church, Whalley Range, gave assistance to my father to make possible the marriage |

|

| My mother's journey to England |

Another sensitive letter from my grandfather. He was told a day or two before my mother left for England of her pregnancy. Of course, with the privilege of a father he could forget his own peccadilloes, how my grandmother had given birth to their first child Fausta out of wedlock, and how my own mother was born only six weeks after his own marriage to my grandmother.

| ||

The first night in England

|

|

| Congratulations from my grandfather's colleagues |

The reference here to Eugenio Schiff led me on a wild goose chase, but it was very interesting nevertheless. This was a mistake of my grandfather for Sir Ernest Schiff who did have his offices at this address, 29 Throgmorton Street, but he died in November 1918. There was indeed at one time a Eugen Schiff living in London, a refugee from Germany. His grandson was extremely helpful to me in my research, though I never succeeded in establishing to which Schiff family they did belong. I placed all my research materials here.

|

| Delivery of their child Valerie. This was before the National Health Service, and was extremely expensive. |

|

| A greetings telegram from my mother's family in Italy on the birth of her first child |

An undated partial letter from my grandfather to my mother. I believe the signatories on the last page must be work colleagues of my mother or her father. In the letter there is a reference to my grandmother that I cannot quite understand, though I have my suspicions. '...mai capire la ragione del suo male. A Tirana credevo di averla capito, ma voi invece di aiutarmi mi avete sempre nascosto ogni cosa facendo il suo male.'

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)